Guatemala :

Through the window of a School Bus

by Katie Thayer

Travelling in Guatemala, even over short distances, is quite an experience for the Western tourist, especially on the “chicken bus”, a notorious feature of Guatemalan daily life.

These colourful, second-class buses can be seen all over Guatemala. Departing from a dirty, congested street on the edge of Zona 1, Guatemala City’s bustling, polluted downtown area, you can catch a chicken bus to most of the main towns in the country, though they also link remote highland and jungle communities between them, hurtling dangerously around the hairpin bends of the Cuchumatanes mountains towards Nebaj, or along the unpaved dirt tracks into the heart of the Ixcán jungle.

Strangely enough, these are actually old American school buses, now presumably considered too old and dangerous, by American standards at least. In Guatemala nothing is too old to be repaired and made use of, and danger barely a concept. The value attached to life is much lower in these parts than it is in the so-called “developed world”; accidental death is much more common, but since you can’t afford to go around worrying all day, you’re better off just accepting the risk and forgetting about it.

Besides, it is not as if you could actually do anything to reduce that risk, or so most Guatemalans would reason. The majority of the population is profoundly Catholic, and believes that what happens to them is basically up to God, and therefore beyond their control. Si Dios quiere (if God wishes) and Con el favor de Dios (with God’s help) are two popular sayings that sum up the prevailing mentality nicely, quite far removed from the Scottish Presbyterian attitude that "God helps those that help themselves", and that your destiny is essentially in your own hands.

Here in Guatemala, a believer’s life is safely in God’s hands, which tends to make you wary of stepping onto buses with too many religious symbols on display - dangling crucifixes, life-size holograms of the Virgin Mary and so on. Nothing could illustrate the Guatemalan attitude towards life better than a ride on a chicken bus, and nothing could be more out of place than the sign above the windscreen, left over from the old days: “The safety of your children is our responsibility”.

Always supposing you are able to tear your eyes away from the road for a few seconds as the driver merrily overtakes three cars and a lorry on a blind bend whilst his associate eggs him on with such words as dale, dale!” (effectively translated as “step on it, mate“), your gaze might alight on a series of small, rather picturesque pink or green crosses by the roadside, indicating where people have lost lives in bus crashes in the past. All the while, the jolly sound of Mexican “norteña” songs, merengue or cumbia played loudly over the radio usually drowns out the sound of the struggling motor, and might even cause you to forget the road ahead, at least for a few seconds.

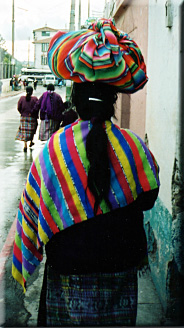

Despite the danger element, there is something appealing about the beautifully painted and painstakingly decorated camionetas, something contagious about the care with which these old school buses have been re-appropriated and transformed. Most have undergone a complete makeover since their past lives many thousands of miles north, having been painted in bright colours, mirroring the colourful clothes of the Mayas themselves. Often, the buses bear female names in the diminutive form, such as Fabiolita, Carmencita or simply Patoja, “little girl” in Guatemalan Spanish.

It seems curious at first to find this combination of femininity and religion in the midst of a very male-dominated, macho world of bus-drivers and their assistants, arguing over passengers and shouting out destinations.

But in a country where men, unlike women, must be strong and not reveal their feelings, worshipping buses that have been blessed with a female identity may be an easy and socially acceptable means of displaying affection. As for religion, it is omnipresent in Guatemala, an integral part of society at every level, and even the most macho of men are permanently haunted by fear of God’s punishment, should they happen to stray from the designated path – hence those religious symbols above the windscreen.

There might be more reassuring ways of travelling (and more comfortable ways, especially for the long-legged Westerner, since these buses were designed for small children!). Yet few would provide you with such a panoramic view of life in Guatemala, on both sides of the dusty window panes, or leave you with such strong impressions.

Inside, there is never a dull moment: as soon as the driver halts for so much as a second or two, the bus is invaded by street vendors, near-hysterical evangelical preachers delivering sermons and charlatans selling you miracle cures for everything from toothache to cancer. Both preachers and charlatans firmly believe they can save you, and both do their best to make you feel you need saving.

Selling what you have to the passengers is a fine art, and many of these people have mastered it to a T. Some of the street vendors claim to be reformed mareros, members of violent street gangs (maras) who have turned away from crime towards more honest means of making a living. For the mareros, telling their life story is an integral part of the selling process, as it makes the passengers feel it is their duty to buy from them in return for the favour they are doing society by leading honest lives.

The ex-marero street vendors rely on people’s fear of violence and corruption. Sadly, it is not hard to induce fear in Guatemalans, especially Guatemalan peasants. Thirty-six years of civil war between the government armed forces and the guerrillas was enough to teach the campesinos (peasants), who were caught in the midst of the political violence, not to take threats lightly.

The US-backed attempt to eradicate “communism” reached a climax of violence in the early 80’s under presidents Lucas García and Efraín Ríos Montt, during the “Scorched Earth” campaign. The idea behind this counter-insurgency policy of the government’s was quitarle el agua al pez, to destroy the fish by destroying the water, the fish effectively being the guerrillas and the water, the population of the areas the guerrillas operated in. This campaign to eliminate all social support for the guerrillas knew no limits, and over six hundred villages were systematically and senselessly burnt to the ground throughout rural Guatemala, under the pretext that the inhabitants were subversives, that is guerrilla members or sympathizers.

During the Armed Conflict, which claimed the lives of more than 200 000 people, over 80 per cent of the victims of massacres and human rights violations were indigenous Guatemalans (Mayas), mostly peasants. Those that survived fled for their lives in the worst conditions, having lost all they possessed, sometimes spending as long as fourteen years in flight in the mountains, or living as refugees in Mexico.

The people of Guatemala have not forgotten what happened to them, nor have their living conditions improved dramatically since the signing of the peace accords in 1996, despite written agreements of compensation, recognition of indigenous peoples' rights and government promises to invest more money in health and education for those in need. In a highly militarised society, social injustice is still alive and well, particularly in the rural areas. Though officially dismantled, the structures of authority imposed by the army during the 80’s continue to exert their power in the villages, and human rights observers still fulfil a necessary task in the areas worst affected by the war, such as the Ixil and Ixcán areas of El Quiché.

Spend any amount of time in Guatemala, particularly in the rural areas, and you will soon become aware of the social unrest. And yet, spend any amount of time chatting to the locals, in the villages, on the bus or wherever, and you will soon find yourself wondering just how it was these pleasant, self-effacing people became the victims of so much horrendous and senseless violence. As Benz put it in Guatemalan Journey, “were these really the subversives the government feared?”

The more I travelled in Guatemala, the further I felt I was from understanding the minds of those who had perpetrated such atrocities. What I discovered, besides a beautiful country of great biodiversity and an incredible range of landscapes and climates, quaint colonial towns and colourful hand-weaved fabrics, was a nation of pacific, unassuming peasants who, like most ordinary human beings, ask for no more than the right to live a peaceful and just life in their own country.

Considering their recent history, it is hardly surprising that Guatemalans barely raise an eyebrow when the chicken bus swerves dangerously to avoid a lorry approaching at full speed from the opposite direction. Many have come much closer to dying in much more unpleasant circumstances, which goes some way towards explaining the common, detached attitude to life. The day the locals start to worry about their travelling conditions as much as the tourists do, they will be a step closer to living the peaceful lives they aspire to.

Copyright © Katie Thayer 2005