THE ANGLO ZULU WAR OF 1879

BY

ROBERT GERRARD FRGS

THE DEATH OF THE PRINCE IMPERIAL

June 1879

In 1870 Napoleon 3rd was defeated in the Franco-Prussian War. Eugenie his wife, and child Eugene Louis Jean Joseph Bonaparte, immediately fled to Britain where they were given succour by Queen Victoria and lived at Camden Place, Chislehurst. In 1873 Napoleon 3rd died following a long illness and Louis became the Pretender to the French throne.

Napoleon 3rd was Bonaparte's nephew. Most of his childhood had been spent in America. Aged 48 he returned to Paris, following the revolution and a year later was elected President of the Republic. By 1852 he had proclaimed himself Emperor and the following year married Eugenie de Montijo, a penniless Spanish gentleman's daughter. Generally the French populace considered them upstarts. The Tsar of Russia was less than polite about the puppet Emperor, but Queen Victoria thought them delightful.

On the 16th March 1856 Louis was born and a 101 gun salute stirred the populace of Invalides early that morning. Louis was known to his parents as Lou-Lou and would begin and end his life as a soldier. His father believed the French would respect a man of military standing more than they would a politician. For that reason, at birth he was enrolled as a Grenadier and within the year held a commission in the Imperial Guard Regiment. At 2 he took part in a military review mounted on a horse. By 14 he was a keen horse and swordsman. But it was the splendour of the uniforms that he loved and the stories of Napoleon Bonaparte. He'd learnt nothing of military tactics. When his father was defeated by the Prussians, he and his mother found refuge in Britain and Louis initially became a lost soul. He saw little chance of returning to France. The Republican Government were pleased at his departure and whatever past he'd had was over and he saw nothing to give him hope for the future. He attended school for one term at King's College in the Strand in London and became bored, returning to Chislehurst to be taught by his tutor, Filon. It was not until 1872 when he went to Woolwich, known as The Shop, the military college for Royal Artillery and Royal Engineer officers, that he began to show any interest in things British. But he realised that in order to be accepted he'd have to prove himself to his fellow cadets; the elite of the British aristocracy; probably little more than 200 families; which he did, accepting his full share of the Rushing that all young potential officers were subjected to, which gained him many friends. Louis graduated from Woolwich in 1875. He'd done particularly well, coming 7th out of a class of 34, receiving the highest grades in his class for horse and swordsmanship, although strangely he only achieved 2nd place to an Englishman in his French examination. As a national of France and pretender to the French throne he could not hold a British commission. But when asked which he would select, had he the option of becoming an officer in the Artillery or Engineers, he was quick to state the Artillery. Meantime the French had noted his success and many were proud of his achievements.

Following the disaster at ISandlwana, reinforcements were required for Southern Africa and many of his friends from Woolwich volunteered. Louis was desperate to go and wrote to the Duke of Cambridge, the Minister of War, pleading his cause. Although Cambridge raised no objection, Disraeli, as Prime Minister, thought it unwise. It would cause political problems with France. Eugenie was then pestered by Louis to approach Queen Victoria to ask her to intercede, which led to Cambridge writing to Sir Bartle Frere and Lord Chelmsford informing them that the Prince would be sent to Southern Africa as an observer, not a uniformed officer, and would be attached to Lord Chelmsford's ADC staff and the letter ended My only anxiety on his conduct would be that he is too plucky and go-ahead. The general thought was, that should he decide to wear a uniform once he arrived, that would be his decision.

The news of Louis' forthcoming departure spread quickly and the French made their feelings known. To a select few in France he was Napoleon 4th and should return to Paris immediately. The Republicans, who had begun to think of him as a serious political threat, were appalled at the thought of a Bonaparte accompanying a British force into a war zone. This was to them worse than Louis being a political threat. On the 28th February 1879 Louis, aged 22, sailed out of Southampton on HMS Danube, accompanied by Xaviar Uhlmann, an ex-French Dragoon who had been his aide since birth, and his valet, Lomas. Uhlmann would not accompany Louis into Zululand, but Lomas would. On the 31st March Louis landed in Durban, where Chelmsford was preparing his military force for the second Invasion of Zululand. The arrival of the Prince Imperial caused quite a stir John Robinson, the editor of the Natal Mercury reported.

He'd arrived in Durban with 2 horses. One had been killed while being off-loaded from the Danube and the other had become ill, and he quickly acquired a mount called Fate. From the lobby of the Royal Hotel in Durban he noticed a magnificent grey mare trotting past and asked Xaviar Uhlmann to purchase the horse on his behalf. The horse belonged to the managing director of Randel Brothers and Hudson, Meyrick Bennet, a relative of mine. Although Bennet was hesitant to part with his horse, he was persuaded and handed over Percy to Louis for 70 guineas, telling him that Percy had a tendency to be skittish. Within a few days Louis had become the main attraction in town. He entertained the townsfolk by mounting Percy from the rear, springing off the ground, grabbing hold of the saddle wallet to settle easily in the saddle. Then he'd supply apples to those watching, telling them to throw them at him, whereupon he'd slice the flying apple in half with Napoleon Bonaparte's sword.

Shortly after Louis' arrival Chelmsford moved his headquarters to Pietermaritzburg and Louis accompanied him. On the 8th May Chelmsford set up his headquarters at Utrecht, where Louis was attached to the staff of Lieutenant Colonel Harrison RE, the acting Quarter Master General. Harrison's responsibilities included the planning of troop movements, establishing campsites and the reconnaissance of routes to be taken by the 2nd Division in their invasion of Zululand. Louis had learnt at Woolwich the art of drawing maps and would be allowed to carry out this function, together with the selection of campsites, while attached to Harrison's staff, although strict written orders had been issued by Chelmsford that he was to be accompanied by an escort at all times when departing camp.

Here Louis met Lieutenant Jahleel Brenton Carey of the 98th Regiment who had been educated in France and spoke French. He was the son of a Devonshire vicar and Louis and Carey were to become close friends. Carey had been in the army for 14 years. He'd served with the West India Regiment and in 1870, he'd served with the British Ambulance Unit during the Franco-Prussian war and then joined the 98th Regiment and completed Staff College before being posted to Zululand. He'd gained a good reputation as a staff officer. Carey's grandfather, Admiral Sir Jahleel Brenton had served with Nelson at Trafalgar.

During his first week at Utrecht Louis was kept busy by Harrison, establishing the exact numbers of men in each unit at the assembly point. Then on 16th May he was allowed to accompany Redvers Buller and 200 men of the Frontier Light Horse on a recce patrol to establish the best route for the Flying Column.

That night they spent at Conference Hill where a small fort was under construction and would be named Fort Napoleon, which boosted Louis' ego no end. The following morning they headed south to Kopje Aleen and crossed the Blood River into Zululand that morning. Later that day a few Zulus were seen near the iNtelezi Hill and the FLH, accompanied by an excited Louis, attempted to round them up, but they disappeared. Buller then saw Louis galloping off on his own in pursuit of a single Zulu who had appeared on the top of the iNtelezi Hill, but also disappeared. Buller was horrified by Louis' lack of responsibility. Galloping off on his own could have drawn his own force into an action for which they were unprepared and he would later advise Chelmsford that he was not prepared to bear the responsibility for the Prince's safety in the future. However the patrol had established a route to iNtelezi, the intended point of rendezvous with the rest of the 2nd Division, who would move north on the 1st June, crossing the Blood River and march 10 miles to the iNtelezi camp site. The move of the 2nd Division north required scouts to move ahead of the Column, and Louis persuaded Harrison to allow him to accompany the patrol in order to complete a sketch of a route map he had started. Harrison despatched Louis to the Cavalry Brigade commander to lay on an escort party to accompany him. Arrangements and orders were given for 6 members of Bettington's Horse and 6 of the Edendale Troop (Durnford's men) to assemble at the staff tents at 9.00am on the 1st June. Harrison did not specially order Bettington to command the escort party, although he assumed he would. That evening Lieutenant Carey learnt that Louis was going out on patrol the following day and got permission from Harrison to accompany him.

By 9.00am on the 1st June the whole of the 2nd Division had started to move, but only 6 of the Bettington Troopers had reported for duty at the staff tents. Bettington had been ordered to take out another patrol but had appointed Corporal Grubb, who was a veteran of 16 years in the Royal Artillery, to command the troop, which consisted of Grubb, Le Tocq; a French speaking Channel Islander; and Troopers Abel, Rogers, Cochrane and Willis, plus a friendly Zulu who knew the area and would act as guide. As the Zulu had no horse, Louis graciously lent him his second mount, Fate. But there were no Edendale men. In the confusion of the Division's move, they had reported to the wrong place. When the Cavalry Brigade commander was asked the whereabouts of the Edendale contingent, he told Carey that most of the mounted natives were patrolling on either side of the advancing Division and, thinking Carey was in command of the escort as Bettington was not present, he should commandeer the first 6 they came across as they rode out. But he added, that as soon as he found the original 6, he would send them as well.

The little party set off, passing Harrison and Major Grenfell of the 3/60th, who also noted the absence of Bettington and the Edendale men. The absence of Bettington did not worry either of them as Carey had obviously been told to take command, but Harrison asked about the Edendale men and Carey pointed ahead saying that they had been told to commandeer 6 from those scouting with the advancing Division. At which point Louis, anxious to get going, spurred Percy into a trot and Grenfell shouted at him Take care and don't get shot. Louis hearing the remark, turned in his saddle and replied Oh no, Carey will take good care that nothing happens to me, and trotted on. As they trotted towards the mounted men escorting the Division, they disappeared, and rather than waste further time, Louis and Carey agreed that the six Bettington men were sufficient to their needs as an escort.

Three hours later they were on a ridge 6 miles ahead of the main Division, looking down into the iTyotyosi Valley, which appeared at first glance to be deserted. Carey suggested it was time to rest their horses, off-saddle and brew some tea. Louis agreed, but failed to dismount. Meantime the others had dismounted, and started to loosen their saddle girths, when Louis pointed out a deserted kraal in the iTyotyosi Valley 2 to 3 miles below them, suggesting the kraal would be a better place to rest - there would be ample material to make a fire. Carey appeared to disagree, but before being able to comment, Louis set off and the escort party hurriedly tightened their saddle girths, remounted and followed. On arrival at the kraal they dismounted, knee-haltered their horses, and Grubb and the Zulu noticed some chewe imfe (sugar cane), at the entrance to one of the huts in the kraal, and that these were still warm from a recent fire close to the imfe. Surrounding the kraal to the south, east and west was a combination of tall grass and mealies, some 6 foot high and to the north, African veld. But nobody posted a sentry. While Grubb prepared the fire, using thatch from one of the huts, the Zulu strolled off to the iTyotyosi River to collect water. Meantime Louis and Carey stretched out on the ground entering into conversation about Napoleon Bonaparte and French politics. When the Zulu returned with the water, coffee and tea were brewed, and the Zulu guide reported sighting a lone Zulu on a rise quite close to the kraal, and a dog skulking on the perimeter of the kraal. Whereupon Carey suggested they should move on. Louis wanted another 10 minutes, but ordered the men to collect the horses which had scattered to graze beyond the immediate area of the kraal.

Once the horses had been saddled and the escort party were ready to mount, Louis gave the order Prepare to mount, everybody placing their left foot in the stirrup. When Louis gave the command Mount about 30 Martini Henry rifles erupted, killing Trooper Abel instantly. Rogers, unable to hold his horse, ran around the back of the hut and was promptly killed with an assegai. Louis was knocked over by the skittish Percy. Getting to his feet, he ran after Percy, grabbed hold of the saddle wallet and attempted to vault into the saddle from the rear. The wallet strap broke and as Percy galloped off, Louis fell to the ground, losing his great-uncle's sword in the fall, and spraining his right wrist. Undaunted, he scrambled to his feet, drew his revolver with his left hand and ran north for about 100 yards, over the veld to a donga. Realising the Zulus were pursuing him, he attempted to make a stand in the donga with his back to one wall.

Meantime Carey and the remainder of the escort party had scattered on their horses, as they'd probably been trained, but failed to rally until they were about 800 yards from the killing ground, when they all realised that not only Louis, but Abel, Rogers and the Zulu were missing, and Carey saw Grubb mounted on Percy. In that moment Carey must have realised that Louis was dead. Stunned at the thought, the 5 survivors huddled together in silence, staring back towards the donga and kraal for a couple of minutes hoping to glimpse the missing 4 running towards them. Grubb had managed to mount his horse, but as his horse had plunged into the donga, he'd lost his rifle. When about to dismount to pick it up, he saw the rider-less Percy next to him, changed mounts and galloped north leading his own horse. The 5 survivors had between them Carey's sword and revolver and 4 rifles. Carey, realising that they were not only out-numbered by the Zulus, but also out-gunned, ordered Grubb to lead the escort party to the iNtelezi

Hill, the intended camp site for the Division that night, and set off at a gallop for the camp himself.

About 4 miles from the camp Carey saw a group of 5 horsemen coming toward him, 2 of whom were the bravest of the brave - Colonel Sir Evelyn Wood and General Sir Redvers Buller - both holders of the Victoria Cross. Buller, seeing the approaching figure galloping towards them said to Wood Why the man rides as if the Zulus were after him. As Carey brought his horse to a halt Buller said Whatever is the matter with you? And Carey replied The Prince Imperial is killed and Buller retorted Where's his body? Carey, totally distraught, merely pointed in the direction from which he had come. Buller, lifting his glass, could see a small group leading 3 horses about 4 miles away and asked Where are your men Sir? How many did you lose? Carey mumbled They are behind me, I don't know. To which Buller growled You ought to be shot, and I hope you will be, I could shoot you myself. Evelyn Wood and Buller briefly discussed whether they should ride to the kraal, but both realised the risks were too great. It was close to dusk and without support they could find themselves in trouble. The little group turned and headed back to the camp at iNtelezi. Upon their return the news was reported to Chelmsford who almost collapsed, before summoning Harrison, Corporal Grubb, Troopers Cochrane and Willis who had survived the ambush.

Meantime Carey had entered the staff mess tent where dinner had started and was greeted by Grenfell Why Carey, you're late for dinner. We thought you'd been shot. Carey replied I'm alright, but the Prince is killed. Within minutes Deleage, a French Republican journalist, who had made a point of covering Louis' every move since his arrival in Southern Africa, demanded full details of the event from Carey and Chelmsford prior to telegraphing the Figaro Newspaper an over dramatic account of the Prince's death, and Archibald Forbes telegraphed the Daily News.

Later that night, Carey, alone in his tent and unable to sleep, wrote to his wife Annie.

My own one,

You know the dreadful news, ere you received this by telegram. I am a ruined man I fear, though from my letter which will be in the papers you will see that I could not do anything else. Still the loss of a Prince is a fearful thing. To me the whole thing is a dream. It is but 8 hours (ago) since it happened. Our camp was bad, but then, I have been so laughed at for taking a squadron with me that I had grown reckless and would have gone with 2 men. Tomorrow we go with the 17th Lancers to find his body, poor fellow! But it might have been my fate. The bullets tore around us and with only my revolver what could I do? The men all bolted and I now fear the Prince was shot on the spot as his saddle is torn as if he tried to get up. No doubt they will say I should have remained by him, but I had no idea he was wounded and thought he was after me. My horse was nearly done, but carried me beautifully.

My own darling, I prayed as I rode away that I should not be hit and my prayer was heard. Annie, what will you think of me! I was such a fool to stop in that camp; I feel it now, though at the time I did not see it. As regards leaving the Prince, I am innocent, as I did not know he was wounded, and thought our best plan was to make an offing. Everyone is very kind about it all here, but I feel a broken-down man. Never can I forget this night's adventure!

My own, own sweet darling, my own darling child, my own little Edie and Pelham! Mama darling, do write and cheer me up! What will the Empress say? Only a few minutes before our surprise he was discussing politics with me and the campaigns of 1800 and 1796, criticising Napoleon's strategy, and then he talked of republics and monarchies! Poor boy! I liked him so very much. He was always so warm-hearted and good-natured. Still I have been surprised; but not that I am not careful; but only because they laughed at all my care and foresight. I should have done very differently a week ago, but now have ceased to care.

Oh Annie, how near I have been to death. I have looked it in the face and have been spared. I have been a very, very wicked man, and may God forgive me! I frequently have to go out without saying my prayers and have had to be out on duty every Sunday. Oh! For some Christian sympathy! I do feel so miserable and dejected I know not what to do! Of course all sorts of yarns will get into the papers, and without hearing my tale, I shall be blamed, but honestly, between you and me, I can only be blamed for the camp.

I tried to rally the men in their retreat and had no idea the poor Prince was behind. Even now I don't know it, but fear so from the evidence of the men. The fire on us was very hot, perfect volleys. I believe 30 men or more were on us. Both my poor despised horses have now been under fire. The one I rode today could scarcely carry me, but did very well coming back. Oh I do feel so ill and tired. I long for rest of any kind. If the body is found at any distance from the kraal tomorrow, my statement will appear correct. If he is in the kraal, why then he must have been shot dead, as I heard no cry. (Enfin nous verrons) Time alone will solve the mystery. Poor Lord Chelmsford is awfully cut up about it as he will be blamed for letting him go with so small an escort. The Times and Standard correspondents have been at me for news, also the Figaro.

My own treasure, I cannot write more. Good night, my own one. I will try and let you know a few words tomorrow. I will now try to sleep, till reveille at 5.00am and it is now nearly one, and so very cold!

The next morning, over a 1,000 mounted men, accompanied by a Battalion of NNC, rode out to find the Prince's body and Carey acted as guide. As they got close to the kraal, the Column spread out. Troopers Abel and Roger's bodies were found close to each other. Both were naked and had been disembowelled. Then Captain Cochraine of the Edendale Contingent came across the Prince's body in the donga. The body was naked except for a gold chain with a clasp of the Virgin Mary and his great-uncle's seal attached to the chain. A few yards away lay a blue sock with the letter N embroidered on it. His body bore 17 assegai wounds, all to his front and sides, 2 of which would have been fatal. One had penetrated the heart, the other had left a scar on his forehead and penetrated his right eye and gone through to the brain. In his right hand was a handful of black hair and his left arm and hand, in which he'd held his revolver, had been slashed. The body and surrounding area was matted with dried blood in which Cochrane spotted the Prince's spurs. The body was lifted to inspect the back as Carey thought he might have been shot within the kraal, but only the 2 assegai thrusts to his side had gone through his body. He'd died in a brave stand facing the enemy. The gold chain was removed and the body wrapped in a sheet and placed on a stretcher constructed out of 4 lances and a blanket and the silent and sombre Column headed back to the camp. That night Chelmsford wrote to Sir Bartle Frere. In that letter he stated that he'd Always felt it unfair that he should have been saddled with the responsibility of such a charge. But I had to accept it with all the rest.

On the 3rd June the embalmed body, packed in a casket, started the long journey back to England. In Pietermaritzburg the body was placed in a zinc coffin, then taken to Durban for the sea voyage to the Cape aboard HMS Boadicea, which set sail on the 11th June, accompanied not only by a military escort, but also by Deleage, Uhlmann and Lomas. At Cape Town, the coffin and accompanying party transhipped onto HMS Orontes and set off for England, where the coffin was off-loaded at Woolwich and placed in a chapel. Later Louis' body would be moved to Chislehurst.

Meantime the news of Louis' death had been received in London on 19th June. The Duke of Cambridge received the news whilst attending a French play at a London theatre. It was Queen Victoria's 42nd Anniversary and she was at Balmoral about to retire when the news was brought to her by her Scottish gilly. The Queen and Cambridge were stunned and both were immediately aware of the political implications. But their greatest concern was how to inform Eugenie before the morning's newspapers reached her. Lord Sydney was given the task and early the following morning he arrived at Camden Place. When Eugenie heard she collapsed and remained semi-conscious for 2 days. That morning Louis' death was blazed across the front pages of the British and French newspapers and both nations were staggered. The French accused the British, and Queen Victoria, of planning his death. Suddenly the whole of France decided they loved the now dead Prince, whom the majority had previously considered an object of derision. On the 23rd Queen Victoria visited Eugenie and during a brief meeting assured Eugenie that her son had died bravely and quickly, which was what Eugenie wanted to hear.

Carey meantime had been subjected to criticism from all his fellow officers, who openly blamed him for the Prince's death. The very thought that they could have been party to a plot to kill the Prince was a blotch to their personal honour. Carey, desperate to clear his name, requested all the facts of the event be made public in an official inquiry, which was held on the 11th June.

A scapegoat had to be found, and the Board recommended that Lieutenant Carey be court marshalled for misbehaviour in the face of the enemy. His court martial convened the following day.

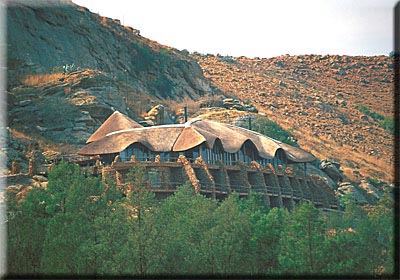

Rob Gerrard FRGS creating the scene and the atmosphere

Rob Gerrard FRGS, the resident historian at ISandlwana Lodge, relates the events of all the battles of the Anglo Zulu War with passion and knowledge as if he had been there. Battles themselves have limited interest, but he brings the characters involved on both sides to life and relating information found in trunks and archives, his audience is spell-bound.

For permission to use all, or any part, of text, maps or pictures, contact Robert J. Gerrard at foxzulu@saol.com.

Copyright © Robert J. Gerrard 2003