Naxos and the Unfinished Temple

Naxos, left un-visited by many a tourist to Greece, certainly doesn’t make any guide books’ top five lists of places to visit. This, coupled with the fact that most of the island is uninhabited, is exactly why we were so excited to settle there for a time during our travels through Greece.

In Naxos, so many things are left and forgotten, slipping away and shifting over on themselves like grains of sand rolling off the cliffs or dispersed by the wind.

Manners, for one - Naxonians posses the most interesting ability to combine European major-city rudeness with the hospitality and kindness of old country values, all wrapped up within each individual person. At their core, I think they have and had simpler values than the Athenians, and a legitimate desire to help. But the fact that the Naxonian tourist influx isn’t as grand as it is in a popular destination like Mykanos, it's only logical that sometimes, you as a foreigner evoke a bit of sass, suspicion, or sarcasm.

Take Logic, for another. If Greece, as Europeans will say, is the land of Paradox, then Naxos is no exception. Pharmacies won't tell you when they're open, only when they're closed. Old men on scooters with radioflyer wagons attached to the back will insist they can give you, your husband, and your 10k a piece luggage a lift into the Hora. No one seems to be sure exactly what year the 2004 Olympics will be taking place, or what to do if mainland Greeks crowd into nearby islands to get away from the throngs of tourists. And should you take the scooter you rent back to the shop owner, telling him that neither the brakes nor the speedometer work, he'll shrug and insist you keep the one he gave you, since after all, "it's only for driving".

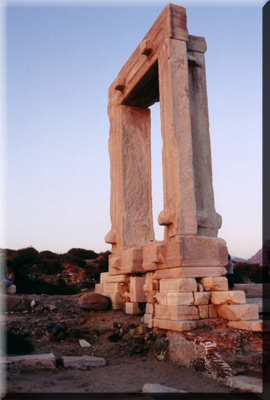

Something striking which cannot be ignored is the unfinished temple of Apollo, which flanks one side of the island. The Portara, or gateway into the temple, stands stubbornly erect, visible from many meters off the island. Seeing it as we pulled into the Port aggravated me - I was surprised to find something I wasn't aware of, especially after studying Hellenic culture, history, and architecture so closely, especially that of Naxos.

Something striking which cannot be ignored is the unfinished temple of Apollo, which flanks one side of the island. The Portara, or gateway into the temple, stands stubbornly erect, visible from many meters off the island. Seeing it as we pulled into the Port aggravated me - I was surprised to find something I wasn't aware of, especially after studying Hellenic culture, history, and architecture so closely, especially that of Naxos.

It was a challenge, we left on the back-burner but never took off the stove, though; it loomed curiously in the background as we wound our days through Naxos, on beaches, in open air movie theaters, in mountains, running through village alleys at sunset.

What I had picked up from conversations about it, if one was to be had at all, was very sparse: the islet at the end of the long causeway, where the temple stood, was called Palatia. The gate, or entrance way to the missing temple was called Portara. This was said to be "Naxos' trademark", but in all my studies I had never come across it.

Of course, being Greeks, there was an opportunity to slam the Turks that couldn't be missed, even within that crumbling ruin: It's said when Constantinople is returned to the Greeks, the rest of the temple will appear. We also heard this line about the church of 1,000 doors on Paros, about the Karyatids in Athens...apparently all of antiquity will be restored to its full Glory if those selfish Turks would just give up the ol' capital.

Slightly amused but no less curious, Steve and I found our way up to the temple one night, frustratingly covered with the few other tourists we’d seen on the island: some chubby German children and people with video cameras who seemed to be filming the weekend away.

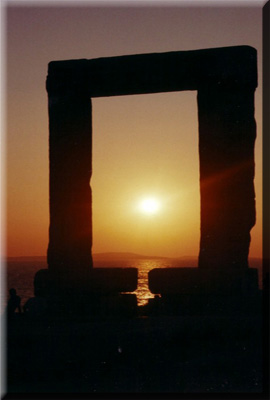

We found a quiet spot on the side of the hill, and contemplated the advertising of Greek sunsets - Santorini, Mykonos, and Crete all advertise - people gather with Martinis and cell phones on some particular wall or another to watch the sunset each day. We didn't think it would happen on Naxos, but maybe the over-spill of tourists from trendy, nearby Ios was to blame.

Watching the sunset through the gate, though, made me suddenly understand the pull - even to those who don't look for it. There is something mysterious about the gate, something deep and natural and human, yet intensely more complicated than that.

Seeing the colors through the temple gate - the oranges, the pinks, the reds - made me think of Histories Mysteries, a show I used to watch as a child on PBS, frightened but riveted by what I saw. Always, the narrator would tell of some far off place with some ancient mysticism attached to it, and emphasize how little we knew now. What secrets does the place hold? How did it all get there? What was its purpose? Why wasn't it complete? Where are the missing pieces? What does this doorway mean? I was proud to find a new mystery of my own, but still a bit frightened for some inexplicable reason, as I had been as a child.

After we'd sat for a while, thinking, taking it all in, we felt overwhelmed. The temple is somehow draining; I noticed that no one who came walking up to the islet stayed more than a few minutes. There certainly was no rule against staying longer, but there was something that gave you the urge to come in, look around, touch, sense, and then leave rather than linger.

We came back to life in the Hora as it goes nightly - restaurateurs trying to offer us their version of a romantic table, vendors selling everything from day-old newspapers to shells, dogs running around, tacky clothing and cigarettes being hawked.

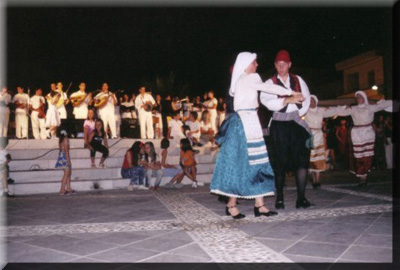

After dinner we stumbled upon a group of locals putting on a show for each other, and they were nice enough to let us stay. It felt good to be restored with some life after feeling the draining pull of the Temple of Apollo. It felt good to dance, feeling the rhythm and passion of folk music blaring from the town’s center, which lies just below the temple.

After dinner we stumbled upon a group of locals putting on a show for each other, and they were nice enough to let us stay. It felt good to be restored with some life after feeling the draining pull of the Temple of Apollo. It felt good to dance, feeling the rhythm and passion of folk music blaring from the town’s center, which lies just below the temple.

When we moved on from Naxos, part of me felt a push to explore the history of the temple gate further – to figure out why it was something that went un-discussed, why it was something that wasn’t as “famous” or as noted in “to do lists” as other, similar structures in Greece. Another part, though, a more powerful, instinct-driven part, realized it was best to let Naxos keep her secrets, and best to just begin new explorations.

Theresa Hunt 2004

Copyright © Theresa Hunt 2004