Caves and Crossbows

Spelunking and Archery with the Hill Tribes

by Antonio Graceffo

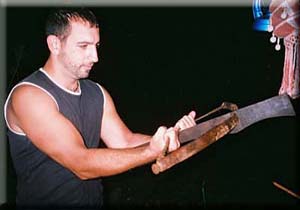

Litee Akha, the champion marksman of Northern Thailand, set the butt of the large crossbow against his flat belly. With both hands, he expertly pulled the powerful string into place. There was an audible "click" as the trigger popped into the ready position. He removed the short bamboo arrow from his mouth, rubbed it with natural bees wax, and set it in the groove, atop the ancient weapon. Holding the bow in a straight line, away from his body, he took careful aim, and pulled the trigger. The deadly projectile flew threw the air, straight and true as any shot ever fired by Wilhelm Tell, hitting the target, dead center.

We all applauded, causing him to smile brightly. His teeth, darkened by countless years of chewing beetle nut, remained invisible in the growing darkness.

The tribal crossbows were surprisingly simple. Both the stock and the bow were fashioned from the same teak wood used to make tribal muskets. The string was made from strands of rattan, which had been twisted, time and time again, making them powerful enough to bend the bow. Unlike in European archery, every aspect of tribal archery is done simply with eye-ball measurements. There seems to be little or no emphasis on exactness. In fact, any attempt to pin Litee down to an exact answer ended in frustration.

"How many times do you twist the rattan?" I asked.

"Until it is tight enough." Answered Litee.

"How many pounds draw does the bow have?"

"Yes." He answered, confusing us both.

I would estimate the draw to be somewhere around 35 pounds. "What sort of animals do you kill with these bows?"

"It is hard to kill animals, because they move too much." Admitted Litee. "But these are great for killing people."

The only moving piece of the cross bow was the trigger mechanism, which was a kind of rocker, fashioned from highly-polished bone. It was held in place by a single peg, made of bamboo. The arrows were short, and cylindrical, as in European archery. But, the fletching was made from pounded bamboo, rather than feathers. The bamboo was split into sections, several inches long, then pounded flat, folded double, and then pounded again. One of the unique things about this type of bow was that the trough, where the arrow lay, did not run the full length of the weapon. It stopped short, three inches from the trigger. This meant that when the arrow was properly set in place, it was not touching the string. The string was already moving, picking up speed, when it hit the arow.

After every shot, the trough was coated with natural bees wax, taken right from a tree. The gummy wax helped to hold the arrow in place, and it lubricated the trough, giving the shot a smooth glide.

Litee went on to say that he did take small

game in the forest, but that big game was actually easier, because their was more surface area to it. He could take a wild pig by shooting it several times. He also enjoyed killing large rodents. All of the hill tribes, and the Akha in particular, will eat any animal. The jungles of Thailand are teaming with some of the most exotic and most endangered creatures in the world. But if they fall into the path of an Akha they will probably wind up in the soup.

The Akha all had slingshots, all had machetes, most had muzzle loaders, and many had cross bows. But they were so desperate for meat, that even while working in the fields they would kill an animal with whatever happened to be at hand, sticks, rocks, or farm implements. They even killed snakes with their bare hands, by grabbing the tail, and snapping them like a whip. These weren't sportsmen. These were fathers, trying to feed their families, the same as anyone punching a clock back home.

"Tomorrow I will teach you." Said Litee Akha. "But tonight, we drink whisky and eat bugs."

Learning to fire a traditional crossbow was something I had always wanted to do. Since coming to Asia, drinking the fiery, most likely poisonous, liquid that the hill tribes

referred to as whisky, has become old hat. But I still couldn't stomach the fried bugs.

My host, Darren, a Brit, was married to a Thai woman, who had grown up near the tribal village. After they were married, they built this house as a weekend getaway. But it soon became a kind of community center for tribal people, who would pop over to watch TV, help in the garden, or in this case, teach archery. Some of the older boys went out into the garden to catch frogs, which would be cooked on the grill. Daren turned on the outside lights, so the village children could catch the thousands of flying insects, who hovered around the bulbs. Once caught, they were placed in a bucket of water, so that they couldn't fly away. Later, the women and children sat on the floor, picking the wings off of the bugs so that they could be fried, and eaten like popcorn.

Luckily, Darren was grilling about 90 kilos of pork, which we had bought in town, earlier in the day. When the bugs were finished, I made some excuse about having eaten bugs for lunch, and tore into the fresh killed pork, like I hadn't eaten in months.

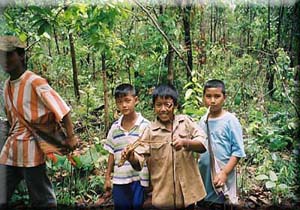

The next morning we manly-men, Darren and I, lead by Litee Akha, armed with cross bows and machetes, set out on our hunting safari. It would have been more authentic, had we been going quietly, on our bellies, like Marines. But instead, we had a gang of about twenty village boys following us, shooting anything and everything with their sling shots. The fun thing about being in the woods with hill tribes is that they find food everywhere. The kids kept scaling trees, or hacking up roots, to share edible plants with us. Of course, the noise was deafening. I would almost rather have been in Bangkok during rush hour.

"If I were an animal I would have run away by now." I told Darren.

"Can you still get your story?" He asked.

"Yeah, just keep the kids out of the picture, and snap a photo of me shooting those water buffalo over there." I said.

"But they are domesticated farm animals." Pointed out Darren.

"The readers won't know that." I protested. "Come on, I'm trying to be Hemingway over here, and you're ruining it."

"They have bells around their necks, and some of them are tied to trees."

"Well, just try not to get the bells in the photos. And, if you can, try not to make me look so fat."

With the whole village standing two feet behind me, snickering, I readied my weapon, and tiptoed up on the water buffalos, or were they oxen? They may have been cows for all I know. Anyway, the photos were somewhat believable.

"Have you got your story, now?" Asked Darren.

"Sort of. But since we are hunting, I would feel better if we had a photo of us actually killing something."

One of the hill tribe boys pulled a badly mangle, dead frog from his bag, and laid it on the ground. To his credit, Litee Akha had much more scruples than me, refusing to shoot the dead animal. But as always, the dollar won out in the end, when I offered to buy not one, but two cross bows, if he would let me photograph him shooting the dead frog. When he went over to retrieve his arrow, he looked like a visitor to a county fair, eating meat on a stick.

"You aren't going to print that." Urged Darren.

"Of course I am. But don't tell anyone it was staged." I said, swearing him to secrecy.

I had learned to shoot a cross bow and how to catch and eat bugs. The hill tribes had learned how to fake a magazine layout. Everyone walked away a winner.

You can contact the author at: antonio_graceffo@hotmail.com

Copyright © Antonio Graceffo 2004