Paddling the Maekok River

By Antonio Graceffo

Chapter 3

I had been told that Headman Tisae, had actually begun doing agro farming years and years before anyone in the west had even thought of the concept. In actuality, all of the hill tribes had historically gone in to the jungle, as hunters and gathers, collecting edible and medicinal plants. What was unique about the hill tribes, however, was that they didn't just use the plants that they found. Instead, they replanted them, in the jungle, near the village, so they would be there when they were needed.

Tisae, had taken the basic hill tribe concept of gathering a step further, by transplanting fruits and other cash crops near his village. Apparently, in the early years of his personal crusade, to both save the jungle and save his people, no one supported him. Not only did the other villagers refuse to help, but they actually laughed at him. But when they began, very slowly, to see the financial benefits, they all joined him. One of the difficulties that men like Rick Barnet face is that the hill tribes are resistant to change anything about their lifestyle. After all, it is there rigid set of morals and cultural norms that have preserved them as a unique people, thousands of miles, and hundreds of years removed from their ancestral home in Central Asia. Luckily, in Tisae, Rick found a willing partner, and both the project and the village were flourishing as a result.

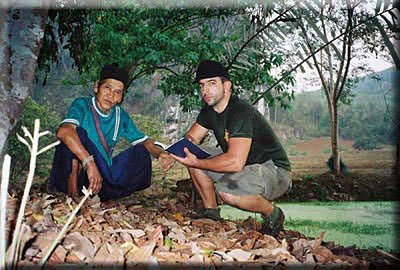

There had been so much build up about this great headman, Tisae, that i expected him to be a regal figure, ten feet tall, clad in stainless, gold trimmed armor, head-to-toe. When word came to us that Headman Tisae had arrived, I was prepared to be awed. Instead, what I found was a comical character, about five feet tall, who lookenk we can do it." I said.

"What about your horrible driving?" He asked.

"We will just have to bring more tires." I answered. The Lahu had already taught me something.d like he had just stepped out of a Disney movie about forest gnomes.

Tisae, who is about 70 years old, had a gaunt face, a ready smile, and boundless energy. He wore a traditional cap, a wraparound skirt, and a machete. Between his spars teeth, stained a deep red, from beetle nut, he smoked, a long, thin pipe, which made him look like some mythical elf from a fairy story. Questions of comportment were mute, as he immediately, led us into the deepest jungle, hacking a path, with his machete. Doing an interview was also out of the question. Tisae talked constantly, Pouk translated, and I struggled through the jungle, writing dictation. The path was steep and narrow, completely over grown with huge thorn bushes, and vines, covered with tremendous spines. The pen might be mightier than the sword. But I would have traded them both for a machete.

Tisae, laughed at the city people, slipping and sliding as we struggled to keep up with the old man.

All Thais, and hill tribes in particular, live by a code of senook (fun). If something isn't senook, they won't do it. By the same token, any work or any hardship is endurable, as long as you make it senook. City people getting cut and tripped up by thorns was definitely a source of senook for Tisae, who cackled constantly, making me wonder just what he was smoking in that pipe of his. He added to his mirth by intentionally cutting the path at a height appropriate for his tiny frame to pass through. The remaining foliage clotheslined any of us westerners, who tried to walk up right, through the forest. At a much needed rest stop, Tisae showed us an ancient tree, which was about four meters in diameter. He climbed up onto the gnarled trunk, and smoked his pipe reflectively. "Look" He said, through Pouk, the interpreter, "I am the spirit of the forest."

Tisae was only joking. But there was much truth in what he said. The hill tribe people really are like spirits of the forest, or maybe children of the forest would be more accurate. These are people who have lived as a part of the natural ecosystem for centuries. Now, because of far thinking men like Tisae, who embrace such modern concept as agro farming, the tribes may survive. In other, less "developed" villages where I had been, I saw starvation and death, as whole villages were on the brink of extinction.

When they told me I was coming to see a farming project, I expected to see fruits and vegetables, growing in nice, even rows. Instead, I found this seemingly virgin trail. Along the way, Tisae would stop and point to some flora and say. "This is a medicinal herb tree. It sells for 300 Baht." or "This is an edible fruit, which we can use to feed the village." Long before the hard science of agro farming came to Thailand, Tisae had the idea of gathering edible and medicinal plants, and replanting them, nearer to the village. Now, through the aid of a westerner, named Rick Burnette, the village has one of the largest agro farms in Thailand. Among crops that Tisae showed us were bananas and coconuts. Once again, he stressed to us that these plants were naturally occurring. But they had been transplanted, within the jungle to provide income and sustenance to the village. The project was immense, covering acres and acres of land. And yet, Tisae told me it only requires five fulltime workers to maintain the project. Growing crops in a natural environment is a nearly hands off activity. "At harvest time," Said Tisae, "The whole village comes to help."

Eventually, the jungle trail, which I had begun to refer to as the "Trail of Tears," gave way to a lowland, where Tisae showed us artificial ponds, stocked with thousands of fish. "How do you feed them all?" asked Anauk.

"Like this." Said Tisae. He took up a huge ant colony, which had been dug out of the forest. He kicked off his sandals, and walked, clinging expertly, on a bamboo which protruded out, over the pond. There, he shaved the ant hill, by hacking it with his machete. The fish all gathered around, below him, to gobble up the tiny feast of ant eggs, which rained into the water.

The tour was over, and the rain began to fall. As much as I couldn't wait to get back to the comfort of the village, and eat one of Pouk's legendary field dinners, the thought of making that same Baton Death March in reverse was so unappealing I began to wonder if I could just spend the night at the fish farm. Tisae, laughing like a banshee, lead us ten feet into the jungle, and set us right back on the easy trekking trail we had used to enter the village originally.

"You mean we could have taken this trail all along, and been spared all the pain?" I asked, in disbelief, and not just a little anger.

Tisae just laughed. I knew what he was thinking. Taking the easy path wouldn't have been senook. Besides, struggling through the forest made a better story. Once again, Tisae taught me that we had a lot to learn from Thailand's Hill Tribes.

contact the author at: Antonio_graceffo@hotmail.com

contact Reinier at: reinier@track-of-the-tiger.com

To find out more about the agro farming project go to: track-of-the-tiger.com

Copyright © Antonio Graceffo 2004