The People of Mekong Island

By Antonio Graceffo

Her hands shook as she poured the watery rice mix into the stone bowl. With effort, she lifted the heavy crank into place, and began to turn. Slowly, with the patience of ages, a frothy porridge of ricey paste began to trickle out of the spout, and into the pail. Seeing that her work was going well, Sae breathed a sigh of relief, and resumed her constant narration. "I takes three cans of rice to fill one bucket. And, I have to turn the crank for one hour." She told me. "When the bucket is full, I will make a batch of rice cakes." The cakes are a favorite treat for the local children. And at 100 Riel each (about two and a half cents) everyone could afford them. "But some of the children don't pay." Said Sae. She tried to look angry, but it was obvious that the kind hearted woman was like a  grandmother of the entire village. And what grandmother

could refuse a cake to a child?

grandmother of the entire village. And what grandmother

could refuse a cake to a child?

Sae sat under a shade tree, in the yard of her daughter-in-law's home. Frail and aged, it was obvious that she couldn't carry water, gather fire wood or do other household tasks anymore. But making cakes was a way she could contribute to her family's income. She felt useful and important. The job also kept her close to her grandchildren, and won her the admiration of all of the village children, who hung around the tree, hoping that the next batch of cakes would not be long in coming. But like everything else in this timeless community, the cakes required patience.

We were on Mekong Island, in the Tone Lesap River, only a few kilometers outside of Phnom Penh. But I felt as if we had traveled back to a simpler, more humane time, when people did not work like machines, and when families could live in close community, sharing with their neighbors. Like in Tevia's village of Anatefka ("Fiddler on the Roof"), every member of the community knew who he was, and what he was expected to do. Sae made rice cakes. The children helped their mothers spin cloth on the traditional silk looms. All of the family members tended to the vegetable garden. And the fathers were mostly fishermen, who worked the waters of the great river, much as their fathers had for generations.

Sae wasn't sure of her birth date, but she believed that she was well over seventy. In her long life she must have made thousands of batches of rice cakes. Even now, Sae told me with pride that she made three batches of thirty cakes per day. "If it isn't raining." She said, with a smile.

The people on the island lived in harmony with the rhythms of nature. When it was raining, they didn't do farming or make rice cakes. When they were tired they rested. When it was dark, they did nothing. With the looms, houses, and farms all on the same plot of ground, the family members were always in sight of one another. The neighbors worked close by, all doing similar jobs. When a vendor stopped by, on a bicycle, selling eggs, the villagers all took this as a sign that they should stop working, and gather around the vendor laughing and joking about the day's events. A few actually bought eggs. Since they all had their own chickens, the purchase of eggs was more a payment for entertainment than it was a necessary purchase. In the same way, when the villagers purchased soap, cookware, or other necessities that they could not make themselves, they did so at the local store. Prices were probably cheaper in Phnom Penh. But Phnom Penh wasn't part of the community. So, the villagers lined up with their motorcycles, to purchase gasoline from a small hand pump, operated by a fourteen year old boy, in front of his parents' home.

Everyone on the island seemed to be doing fairly well. Between their fishing and gardening, they had enough to eat. And the silk business brought in some cash for the purchase of other necessities. My host on the island was Nunse Pai, the daughter in law of Sae. Nunse Pi was one of the new generation of island dwellers, with one foot in the old economy and one in the new. While her family did traditional business, her husband was not a fisherman. Instead, he had a much coveted job as a security guard at the American Embassy. If they moved to Phnom Penh the family would still have been well-off, and the father would not have to commute by boat each day. But the family loved the island life style. And, by remaining on the island, the family could supplement their income with farming and silk trade. By island standards, Nunse Pai's family was wealthy.

As always in Cambodia, terms of wealth had to be seen in perspective. Buyers came to the island each day to purchase the day's silk production. The silk sold for 3000 Riels per kilogram. With an average family producing 1.5 kilograms of silk per day, the cash income of most family's would be about $30 per month. Alone from her husband's salary, Nunse Pai's family received $150 per month. She told us that a silk loom cost $40. And that with her husband's income she hoped to buy more looms.

A fisherman named Noy agreed to take me and my translator, Sawat, on the river. The boats were fashioned from a single palm tree, and resembled traditional dugout canoes, with no draft and very little distance from the board to the water surface. The boats were driven by a man perched, precariously, on the absolute bow and aft point, using a long poll to punch the boat along. Originally I had wanted to pole the boat myself, but I quickly realized that I lacked the dexterity to stand in the boat, much less to operate it. The island men had spent the whole of each day on a boat, since they were very young. They made handling the boat look like child's play.

On the water we talked to some fishermen who had been making their living in the same manner for generations. They all told me that they earned about $1.50 USD per day. They also said that the fishery police would periodically come around and take some of their catch. On the surface it sounds horrible to steal from some one who only earns $1.50 per day. But in the somewhat confused state of Cambodian economics, the police only earn between $10 and $20 per month. There are no income taxes in Cambodia. In fact, there are almost no, legitimate, enforceable taxes in the western sense of the word. As a result every business person contributes to government salaries directly by paying "tax" to government officials. If it weren't for these "taxes" government officials couldn't feed their families.

One westerner, who owns a cafe told me, "In a way, Cambodia is more honest than the west. In the west, you pay a faceless tax, which gets deposited into the general operating fund of the government. This money is supposed to pay the salaries of government workers. And yet, teacher salaries are terrible. At least here, you know the money is going right to the government employees." She said that she liked to think of this as a "direct tax system."

The other complaint I heard from fishermen and the silk weavers alike, was that the Vietnamese were taking business from them. The fishermen claimed the Vietnamese had faster, better boats, and could catch more fish than the Khmers. So it was getting harder for a Khmer to make a living. The silk weavers said that the Vietnamese could make excellent silk, and that they were selling it cheaper than the Khmers.

In Cambodia, every aspect of life, no matter how mundane, is an allegory, in miniature, of the entire Khmer society. Just asking a subsistence fisherman about his day brought tales of government corruption and Vietnamese domination.

We stopped to talk to a family of Cham, who lived on their two fishing boats. The Cham are Muslims, who have lived in the region for centuries, but who are not ethnic Khmers. They follow a version of Islam, which differs dramatically from that practiced in the Middle East. They have their own language, but I was not able to ascertain if it was Arabic, or some, unique Asian language. Sawat would often get frustrated while translating for me, saying."They are speaking Cham again." As far as I know about Islam, regardless of what language they speak, the practitioners are all expected to read Arabic, and the Koran should be written in that language.

When I asked the Cham family about the Arabic language, they just shook their heads, not even knowing what it was I was referring to. I rephrased the question and asked if the Holy book were written in Khmer or in another language. The father smiled proudly, and sent his daughter into the covered part of the boat. When she returned, she handed me a very waterlogged, and weather beaten book, which I assumed was the Koran. It was written in Arabic script. I asked if they could read it, but the father and mother both laughed, saying "We can barely read Khmer. We can't read this book at all."

Many Cham are born on boats, and spend their entire lives on the water. They only come ashore in order to attend services at the Mosque. I would assume that literacy among Chams is probably as low or lower than that of rural Khmers. Although extremely peaceful today, the Chams face a great deal of racism, because of the ancient history of Chams battling the empire of Angkor. The Poll Pot era was particularly hard on Chams, who Poll Pot sought to wipe off the face of the Earth. A much higher percentage of Chams, than Khmers, were killed during the Khmer Rouge time. For those who survived, like the mother and father of this family, those four years that they were forced to work as farmers are a horrible memory. The water-born Chams don't feel comfortable on the land, neither are they used to the back-creaking toil of farm work.

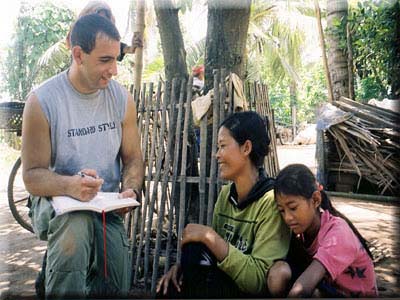

When we returned to the island Sae's family approached us, looking very shy, and apologetic. After many Sampeas (hands held in prayer position, as a sign of respect) and much talking around the subject, but never broaching it, they invited us to lunch at their home. When I asked Sawat why the family was so shocked that I accepted, he told me. "They have never seen a foreigner before. And they were afraid that you couldn't eat Khmer food."

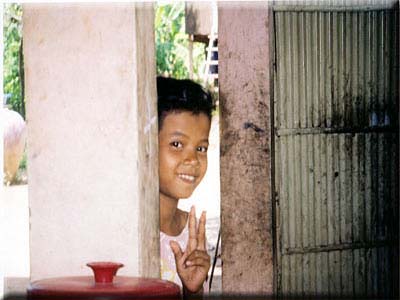

Of course, the food was excellent. The children were very cute, keeping their distance at first, but then slowly coming over to stare at the exotic being from another world. Eventually, they all posed for photos, as did all of the neighbor wives. I was in the middle of teaching the kids to box, when Sawat said it was time for us to return to Phnom Penh.

My day spent on Mekong Island was more of a cultural experience than a year in Phnom Penh. Sae and her family didn't understand why I told them I was grateful to them. And that may be their most endearing quality. They were good, kind people, who didn't know they were good or kind.

Copyright © Antonio Graceffo 2004