Taklamakan Desert by Rickshaw

The Taklamakan Desert, also called The Desert of Death, is located in China's Xinjiang Province. It is the second largest desert on Earth. Scientists consider it to be the most dangerous desert in the world. My plan was to travel 544 km, under my own power, along the famous Silk Road, from the oasis town of Aksu to the oasis town of Kashgar.

The Journey began at the train station in Urumchi, the capitol of Xinjiang, where the Uyghur, a Turkick people, who follow the religion of Islam, make up more than 50% of the population. Many Uyghur men wear skull caps and a knife in a sheath on their belt. Women wear headscarves, some were completely veiled.The sights, the sounds, the smells of the street in the Uyghur capitol are reminiscent of anythingbut China. It could just as easily have been the bazaar at Marrakesh, circa 1600.

The rickshaw salesman asked me, "What kind of rickshaw do you want?"

I gave him the one criteria I insisted upon. "Give me a red one."

I also had a choice between large and small. Since at this point I still wasn't sure if I was just playing an elaborate practical joke, I bought the smallest one they had, to save money. This way, if I got two miles out of town and quit, I wouldn't be out so much cash. The problem with the small sized rickshaw, however, was that it fit me like a clown car in the circus. It was hilarious seeing this 200 LBS caucasian with a New York Yankees cap trying to ride a tiny, three wheeled bicycle, with a barbie doll camper in the back.

An hour later I had loaded up the rickshaw with food, water, and my gear. The whole hotel staff came out to see me off, and to get a look at my crazy vehicle. They were all laughing and smiling, but still suggested. "Wouldn't you be more comfortable riding the bus?" They just didn't get it.

I made it about three blocks, when I realised I didn't know how to get to Kashgar. So, I rode back and asked directions. A truckdriver drew out a map on the back of a cocktail napkin, and off I went again.

I made it over 500 KM! The first day I rode for four hours. It was around eight o'clock, and I needed to get out of the sun. But in the desert, there was no shade at all. There wasn't even anything that cast a shadow. I found a power pole with a brick base. The base was one meter wide by one and a half meters high. If I lay on the ground, and curled up in a fetal position, the shadow just about covered my body. I stayed like that till sundown. The sun doesn't set until about 11:00 PM in the desert. So, I had a long wait. I was eaten alive by mosquitoes, and spent a fitful night.

I made it over 500 KM! The first day I rode for four hours. It was around eight o'clock, and I needed to get out of the sun. But in the desert, there was no shade at all. There wasn't even anything that cast a shadow. I found a power pole with a brick base. The base was one meter wide by one and a half meters high. If I lay on the ground, and curled up in a fetal position, the shadow just about covered my body. I stayed like that till sundown. The sun doesn't set until about 11:00 PM in the desert. So, I had a long wait. I was eaten alive by mosquitoes, and spent a fitful night.

The second day, I got the hang of riding the bike, and rarely went off the embankments or ran into cars. A construction crew invited me to their camp to eat lunch, and take a nap.

I learned to sleep in drainage tunnels under the highway or under the railroad. I ate the food I brought from Aksu, dried sausage and Uyghur bread. Almost every day I managed to buy water and one hot meal in a Uyghur village. Usually the Uyghurs eat bread and goat meat or goat meat soup.

The most memorable day was the sixth day. There was a twenty mile an hour head wind, which lasted for five hours, and which pelted me with sand. The wind didn't come in gusts. Instead it was one long, continuous force of hot air, blowing mercilessly in my face and eyes, like walking into a hair dryer. It was so strong I had to walk most of the way, dragging my rick shaw. Unfortunately the big bike acted as a sail. When my grip weakened the bike actually blew away from me. This was also the only day that I ran out of water.

I was panting from exhaustion, which meant my mouth was open, and the hot, wind-born sand was drying out my tongue. It was the closest to hell that I came. After the sand storm Uyghur workers invited me for dinner, and to stay the night at their camp.

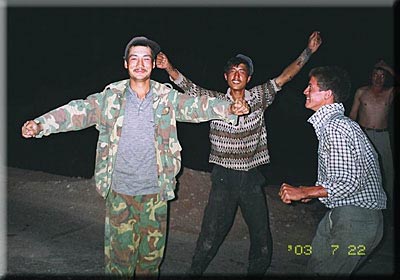

TheUyghur workers played a duodar, a stringed instrument, and a drum. While they sang, we danced and whirled out in the desert under a huge sky, where the stars burned as bright as a reading light. It was magic, and definitely the happiest moment of the trip.

The final 45 km to Kashgar were interminable. My bike began rattling apart. First the carriage jumped off of the rear axle. Then the handlebars came loose, and began rotating, like a radar antenna. The final day was also the day of the most intense sun I had seen during the whole trip. I actually heard the cytoplasm in my brain boiling.

Far off to the right, across an expanse of about 1 km of barren desert, I thought that I could see a huge, cool lake glistening in the sun. I wanted nothing more than to, run over, and jump in. Assuming I was just hallucinating, I tried to ignore it. But, no matter how long I rode, this lake kept beckoning me.

What appeared to be one 1 km of straight line distance across rolling sand dunes could easily have been ten times that distance once I actually started walking. That would mean the walk to the river would have taken hours. It would have required at least a liters of water. And what if I was wrong? What if there was no river there?

In the end I took some advice from an old paisano. In the diaries of his travels, Marco Polo had warned that all along the Silk Road the traveler would hear voices and spirits beckoning him to abandon the path, and walk into the desert.

He would then loose his way, and die of thirst. Rejecting the promise of swimming in a cool lake, probably full of ice cream, I twisted my wayward handlebars back into position, more or less, and continued to Kashgar.

No one gave me a parade or a medal when I got to Kashgar. The trip was over. But the Journey continues. I remember my hero Dan Eldin whose biography is called. "The Journey is the Destination." It's not about achievements or rewards. It is about having an interesting life along the way. Next spring I plan to be the first American to cross the interior of the desert from South to North, with a camel.

Antonio Graceffo 2003

Copyright © Antonio Graceffo 2003